Smallholder Farmers in Africa: The Case of Tanzania (Part 1)

The persistent problems of food insecurity in Africa have led to widespread malnutrition and famine across the continent, it is stated that one out of four undernourished individuals in the world lives in Africa (Blein et al., 2013). In the following two blog posts, I will be looking at smallholder farmers in Africa, specifically in Tanzania.

Agriculture employs more people than any other occupation on the planet, and the agriculture sector in Tanzania contributes considerably to the economy, employment generation, and food security. Tanzania is one of the SSA countries where agriculture forms the backbone of the economy, accounting for approximately 45 percent of GDP, 60 percent of merchandise exports, 75 percent of rural family incomes, and 80 percent of the population employed in agriculture (Andersson et al., 2005; United Republic of Tanzania,2011). Rice is the major food and cash crop in Tanzania, as acknowledged by Agritrade (Rugumamu, 2014) and Kafitiriti et al. (2003), the country ranked second within Eastern, Central and Southern Africa in terms of rice production and consumption after Madagascar.

Impact of Climate Change

Despite the promising trend in rice

production and exports, Tanzania’s agriculture sector is heavily dependent on rainfall. Variability is the keyword to Africa, the unpredictability of

precipitation patterns and timing of rainfall would exacerbate the challenges

for rain-fed agriculture, which is the dominant method of agriculture in

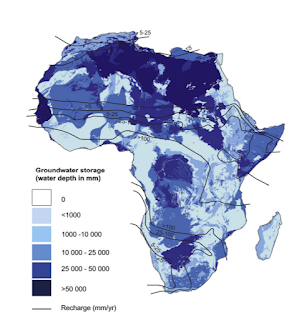

Sub-Saharan Africa (Taylor, 2017). This has significant implications for the water

supply that is available for food production, and climate change will bring

about substantial welfare losses especially for smallholders whose main source

of livelihood derives from agriculture.

Several studies have explored climate change using General Circulation Models (GCMs) for Tanzania, with projections indicating a drop in rainfall throughout central Tanzania and an increase in rainfall over the Lake Victoria region. (Mwandosya et al., 1998). Temperatures in Tanzania are projected to rise by 2-4°C by 2100, warming up the interior regions of the country during dry periods (Hulme et al., 2001; Paavola, 2008; Tumbo et al., 2010). The impacts of climate change on Tanzania agriculture are clear. Interior areas of Tanzania will have a reduction in precipitation of up to 20%, prolonging the dry season and increasing the risk of drought; the eastern part of the country will experience increased rainfall events by up to 50%, increase the frequency and intensity of floods (Kahimba et al., 2015). Tanzania's main cash crop, rice, is farmed in three major ecosystems: rain-fed lowland, irrigation, and upland rice, with each kind characterized by a generally low but varied production capacity depending on soil and climatic circumstances (Kato, 2007). Drought, floods, strong winds, and excessive rainfall generated from changing climatic patterns have resulted in a decline in crop productivity (Rowhani et al., 2011). In severe drought years, performances of local drought-tolerant cultivars are poor and the loss of yield production is reported to be as high as 50% due to drought-related stress (Kahimba et al., 2015).

Perceptions of Smallholder farmers

Although smallholder farmers in Tanzania perceive and recognize the presence of climate change, they failed to take actions to cushion themselves against its adverse effects. One major issue for this failure of adaptation and mitigation is the education level of individuals. With respect to education, highly educated farmers have undertaken adaptation to climate change such as changing planting time and using crops that are more resistant to drought and flood events, and farmers with lower education levels failed to realize the importance of such adaptations. For smallholder farmers, it is really difficult for them to adapt immediately to the change in climatic conditions due to the restraints in their farm sizes. For example, farmers with large farms tend to not use the planting tress strategy as an adaptation to climate change because it is just too costly for the scale of land. Furthermore, as farm size increases, the likelihood of farmers adjusting to climate change by changing planting dates reduces. Farmers with larger farms can diversify their risks from climate change by growing multiple varieties of cash crops, which results in a 3.8 percent lower likelihood of changing planting dates (Komba and Muchapondwa, 2012).

Many concerns remain unanswered about how

smallholder farms might adapt to changing demand patterns and the impact of

climate change on water resources.

评论

发表评论